I was given the title "Aspects of Water Quality" and asked to cover far more than I had time to.

So I quickly rattled through the first bit and focused on ions in water and liquor treatment.

I'd co-authored some papers on brewing water and liquor treatments for Brewers of Europe so was quite clued up on the subject.

|

| You can also add sodium metabisulphite |

- Brewing water: the ingredient, needs treating.

- Process water: washing, sterilizing, pasteurisation refrigeration. Should be potable and softened.

- General purpose water: Washing down and office use. Should need no further treatment.

- Service water, boiler feed. Should be softened and ideally demineralised.

Now to get to the meat of the matter. First you need to get your water analysed in a laboratory for mineral ion content. You can an analysis on the website of your water company nowadays, but water supplies can change so it's still best to get your own analysis. I know Murphys, who supply liquor treatments will do a free annual analysis for their customers.

You can do some analysis easily yourself, tasting and looking at the water before using it. Measuring the pH isn't of much use for telling you how to treat your water, but a change might alert you to the fact the water company has switched to a different supply. There are kits you can use to do your own testing, which you can get from supply companies or even from aquarium shops.

Back before people had learnt how to adjust water chemistry different places became known for doing different types of beer their water was best for: Burton-upon-Trent for pale ales, London and Dublin for porters and stouts, Munich for dark lagers and Pilsen for pale lagers.

|

| mg/l is the same as ppm for those of you watching in black and white |

The different mineral compositions in the water affects the pH of the mash, as does the grist composition with roasted grains lowering the pH. If brewing liquor comes from the brewery's own source it will need to treated to bring it up to drinking water standard.

As bicarbonate is generally bad for brewing it is likely it will need removal and there are several ways this can be carried out.

|

| Temporary hardness that is |

Reverse osmosis and deionisation require expensive kit. The most common method used in small breweries is to add acid, represented by the 2 H+ ions in the lower equation. They react with the calcium bicarbonate, Ca(HCO3)2, making water, H2O, and carbon dioxide, CO2.

It's also common to add mineral salts (to the grist rather than the water) to get the calcium level up. Calcium sulphate (gypsum) and calcium chloride are the most commonly used.

Calcium has a number of beneficial effects, the only real negative is that as it lowers mash pH it decreases hop utilisation:

Magnesium, like calcium, will reduce wort pH but it is only half as effective.

Table salt (sodium chloride) is included in some liquor treatments, but I suspect mainly as a cheap way of increasing the chloride concentration.

The balance of sulphate and chloride ions is considered important due to the effects it has on beer flavour.

Though the research I found on it suggests the effects may not be huge:

Generally zinc is the only element that wort may need supplementing with.

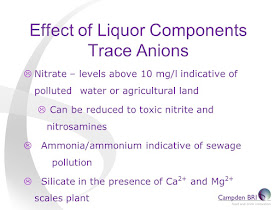

The anions (negatively charged ions) listed here get frowns across the board:

And now to the maths. It is possible to do some calculations to work out how many grams of mineral salts you need to add to get the desired ionic concentration in wort. Calcium sulphate will also contain some water which needs to be factored into the calculations.

Having calculated how much calcium sulphate we need to add to get the desired calcium concentration we then see how much sulphate this adds:

Similar calculations can be carried out for calcium chloride. There are also calculators online that can do this sort of thing for you.

A useful way of looking to what liquor treatment brewing water will require is to calculate the Residual Alkalinity. By working out how much the calcium and magnesium present in the water will break down the bicarbonate it is possible to determine the Residual Alkalinity that may require further treatment.

A multi-national company I brewed for whilst I was at Campden BRI went for very simple liquor treatment for all beers: use Reverse Osmosis water and add gypsum to the mash to give 100 ppm of calcium.

The basic requirements for brewing liquor ion composition have been summarised quite simply:

|

| Sulphate/chloride ratio to taste! |

Pilsner: -35 to 35

Light beer: less than 90

Dark beer: less than 180

There is information out there. The water book is over long and rather dry* but does contain a lot of information. I wouldn't recommend reading it cover to cover, just look up the chapters you need.

The Handbook of Brewing contains a good chapter on water, and is now up to its third edition.

Supplies of liquor treatment are of course also a good source of information on the subject, unlike the SIBA technical helpline which had the plug pulled on it.

*Yes, I even managed to work a joke into a talk on brewing water. Not a great one I'll admit, but you can only work with the material you've got.

Per the water composition for different beer styles, would you say those amounts are still accurate for what UK brewers are targeting today?

ReplyDeleteThey're fine, but there are now some people doing different things for new beer styles (e.g. cranking up the chloride for low bitterness NEIPAs).

Delete